Glimmerglass State Park Ansel Adams and More at the Fenimore Art Museum

Cooperstown, New York The Historic Village at Cooperstown

In my last post, I visited the Fenimore Art Museum which is the showcase of the New York State Historical Association. If you want to know about the museum and the man responsible for it and for the revitalization of Cooperstown, check out the previous post in blue above.

The totem pole taking center stage out front on the museum’s lawn looks rather out of place but I love totem poles so I’m happy to see it.

After I park my car I go up to check it out.

The information plaque tells me that the Fenimore Art Museum is home to the Eugene and Clare Thaw collection of American Indian Art. I did not know this. I had come to see the Ansel Adams exhibit.

This collection is one of the most renown collections of American Indian art in the world. To quote the museum “These objects are the best of their kind – milestones of creativity that stand on their own as exemplary works of art”. As I mentioned in my previous post, It is a huge exhibition taking up most of the ground floor of the museum. Thus it requires a post of its own to even show a portion of it.

First, the totem pole.

This totem pole commissioned by the Thaws from Haida artist Reg Davidson was given to the museum in 2010. Davidson chose a 30’ tall 4’ wide cedar to tell the story of Raven stealing Beaver’s house. The main figures on this pole from the bottom up are: Beaver holding a stick with his checkered tail turned up in front of him; the Raven holding the beavers house in his long bill; the hooked beak Eagle, a main Haida family crest; topped by the black finned Whale – one of the artist’s crests. Small secondary figures, the spirits of the animals made visible, are seen at the bottom and in between the main figures. In the traditional Haida story, the Raven (a notorious trickster) steals the Beaver’s house, lake and fish trap and teaches the Haida people how to catch fish.

As you come down the beautiful staircase from the entry level,

the collection is right in front of you. It is entitled

“Traditions of Celebration and Ritual”

Inside, the collection boggles the mind. So many objects from so many tribes all over North America from Mexico to Alaska and the Northwest Territories.

Buffalo Robe Painting 1820-1840 Arapaho Wyoming. This is a woman’s Buffalo Robe featuring geometric designs. A man’s Buffalo Robe like the one following would feature images from his battle exploits.

This robe dates from around 1880 Lakota (Teton Sioux) North or South Dakota. Robes were worn over and around the shoulders, hanging to mid calf, overlapping in front with the animal head to the wearer’s left. The war records on this skin, finely drawn by two different Teton Sioux artists, record warfare between the Sioux and the Crow.

The colors are amazing. I wonder how the collectors got these.

This jacket dates from 1800 in Manitoba, Manitoba Cree. It combines the ancient tradition of geometrically painted moose hide with a European tailored cut and glass bead decoration. This is unusual since most Native garments were pulled over the head to prevent the loss of precious body heat from the front opening. The elaborately beaded shoulder decorations appear to be a Native interpretation of traditional military ornamental shoulder pieces.

This Lakota spoon from 1890 depicts a Crow Warrier’s stylized face on the top of the handle. The warrior owner would have used it on special occasions to suggest his enemy was at his service and presenting him with the riches of this feast.

The bead and quill decoration indicates that this was a feast spoon and it must have gone in some very large kettle or pan judging from its size. I took the picture with the people standing behind it so its size would be apparent.

Another Nakota 1870 feast spoon has an intricately carved horse head and mane. This ladle was carved from a buffalo horn that was steamed and bent into shape.

In this display the face in the back is on a fragment of a feast bowl that was over 14’ long. It was made in Kwakiutl British Columbia around 1890. The bent corner box in the front row is from Haida, Haida Gwaii, British Columbia or Southeast Alaska around 1780

The artist created the sides of this box from a single plank. To form the corners he cut three wedge shaped grooves on the inner surface, soaked the plank in water, steamed it, bent it into 90 degree angles along the grooves and then lashed the two ends together with a cord. When filled with roasted salmon, cooked roots, or mixed fruits and berries for feasting the bulging sides would appear as a metaphor for the bounty being distributed by the host families.

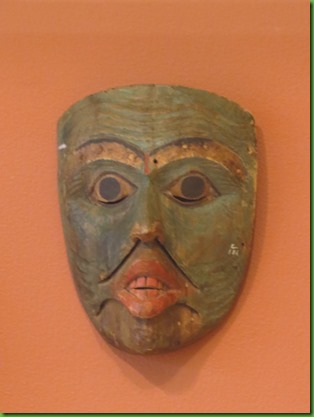

There are clubs, masks, dagers, jewelry, bowls, baskets, woven jars and root bags, pottery. The space and artifacts seem never ending. I’m leaving out twice as much as I’m showing. I am amazed at the colors still remaining on these 19th Century masks.

Tlingit 1830-1860 Southwest Alaska

Nuu-chah-nulth ca 1820-1870 west coast of Vancouver Island

Windmaker mask ca 1890 Central Yup’ik, Alaska.

Mask uses caribou fur to symbolize the breath of the spirit.

Perhaps frosty breath on a cold day.

Raven Mask ca 1850 Central Yup’ik Alaska

S’xwaixwey Mask Salish Northwest Coast ca 1900, the S’xwaixwey is the most prominent and well known mask among the Salish People. It’s eyes project on salks like the eyes of a crab or a snail, its nose is the head of a bird and its horns are also birds’ heads. The mask is danced at polatches, puberty ceremonies, weddings and funerals.

Many of the masks have a bite plug attached to the upper lip on which the dancer bit down to hold the mask in place

Necklace ca 1200-1400 Salado Culture Central Arizona. Made of spiny oyster shell, turquoise, clamshell and pitch

These weavings and pottery are also from the southwest.

On his Zuni jar, ca 1900, the image of the deer has a red heart-line extending from the mouth to the chest area. This is the heart-line, the spiritual essence of the deer.

This is a rare Santa Ana water jug ca 1830-50. It is distinguished from other Pueblo pottery by its elegant, accented oval shape.

Not only are the artifacts beautiful, the space in which they are displayed is as well. I love glass above and around but especially the view through the display cases and out the window. The views blend perfectly with the natural world in which these artists lived and made these marvelous objects.

Obviously the view is much richer in color in person. The windows are spotlessly clean.

The Tlingit often carved house posts made to stand before and fasten to an interior post which supported the roof of large clan houses. This preserved the posts and allowed them to be moved from one house to another. These posts are from the Tongass Tlingit, Taguan Village in Port Chester Alaska ca 1820-40. The carvings usually represent the crest emblems of the particular clan, in this case the Raven clan. The Raven carrying the sun in his beak is one of the oldest in Tlingit mythology.

The history told here is that Raiding Tlingits from the north attacked the area in the late 1840’s destroying many of the homes and driving the people to other areas. In 1920, the posts were taken from the long abandoned village to Seattle and preserved in a local club. No idea if the collectors found them there or bought them from an auction or dealer. They are HUGE and very impressive.

The Thaw Gallery is a sub group of subrooms off of the main area.

American Indian Culture is an immense subject. There are many ways of organizing and trying to understand its variations. The most common is by geographical area as Native Americans lived in close relationship to their environment. This section of the Thaw Collection is divided into cultural areas: Eastern Subarctic, Northeast Woodlands and Southeast Woodlands; Plains, Prairie and Plateau; Southwest Great Basin and California; Northwest Coast; Western Subarctic and Arctic.

I read that the theme of the Gallery is artistic quality and that has been evident from the first piece I saw. Each piece has a T number on its label and you can use these numbers to find out more detailed information. The numbers refer to the inventory sheets which are accessible by computer and in binders located in the Study Center on this same floor. I really wish I had time to look up a few of these to see if they indicate how they came to be in the collection.

The map illustrates these regions and identifies the tribes represented by the objects in the collection. This is amazing to me. So many tribes, such a huge area and to think that these are not all the tribes which were living on this continent when Cristoforo Colombo “discovered it”.

I’m amazed to see works from ancient Woodlands and Mississippian Cultures which date from 300 B.C. like this Effigy Bowl made of Shell Tempered Clay and found in St. Francis County Arkansas. This is some of the most striking pottery in North America. It features an elaborately decorated human face and an intricately detailed ceremonial mace.

This Gorget Neck Ornament ca 1200-1350 Caddoan, Oklahoma, Spiro Area, Mississippian Period was made from a Busycon whelk shell, a marine shell traded from the southern Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

Leggings ca 1880 Teton Sioux (Hunkpapa), North or South Dakota. Made from hide and glass beads. The quality of the work in every single piece is simply spectacular.

Robe 1850 Tlingit, Southeast Alaska, Mountain Goat Wool, Cedar Bark and Native dyes.

Tlingit men and women collaborated to make Chilkat Robes which were worn for ceremonies and special occasions. Men painted approximately half of the robe’s symmetrical design on a pattern board. Women used the board for reference when weaving the garments. They finger wove the robes using a complex braiding and twining technique that allowed for curvulinear designs. The depiction of a diving whale is crest imagery that identified the ancestral line of the family.

I just have to stop and stare in amazement at the artistry in this work. How long must it have taken to weave? How did the family lose it?

The gallery is not all about the art works of the people we displaced. The museum has a room I can see through the cases with photographs of the Native People of the 21st Century lining the walls.

This is the last room I visit in the Gallery and I am very glad to see it here. It is important to remember that these people are still here and still fighting to defend their lands. The room is lined with photographs from Matika Wilbur’s (Tulalip & Swinomish, Washington) 562 Project.

Matika is a fulltimer. In 2012 she sold everything she owned, left her apartment in Seattle and set out on the road to photograph members of all federally recognized tribes in the United States in their home territory . She says her goal is to “unveil the true essence of contemporary Native issues, the beauty of Native culture, the magnitude of tradition and expose their vitality”.

She says she hopes the pictures she’s taking can someday replace the stereotyped, dated ones found in internet searches, and the ones we hold on to in our collective psyche.

“I’m ultimately doing this because our perception matters,” she says. “Our perception fuels racism. It fuels segregation. Our perception determines the way we treat each other.”

Here are just a few of the people who line these walls. The stories of these people which accompany their photgraphs are powerful and I urge you, if you have the opportunity, to see Project 562 for yourself.

As I leave the gallery I pass through the main room and once again enjoy the beautiful buckskin dress which draws your eyes from as you walk through the doorway.

Women’s dress ca 1850, Nez Perce, Idaho, Oregon or Eastern Washington. This striking deerskin dress is made from two deerskins. The artist sewed bands of rich beadwork across the upper area of the dress and attached long slender fringes at the bottom. Elegant seems the perfect word to me.

Thanks for sticking with me through such a long post which is truly only a very tiny sampling of what this collection has on display. It is is the second most amazing collection of Native American Art I have ever seen, second only by the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

These are antiquities and I am honored to have been able to see them but throughout I have been haunted by my feelings that these belong in the families of those who created them and not in a museum created by ancestors of their conquerors. Perhaps the tribes from which these beautiful pieces come would be happy to have them here, well preserved and admired but I think the tribes should be contacted and asked and the items repatriated if they request. Yes, I asked about repatriation but none of the staff working today knew what it was.